World leaders are falling in love with the idea of negative rates to save us from a global recession, but can negative rates save the global economy?

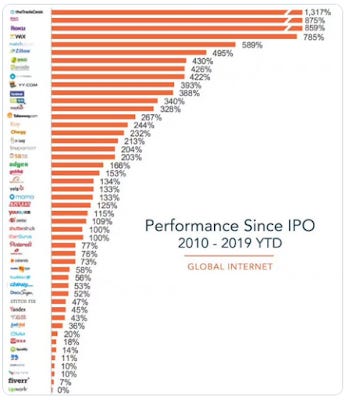

After much research, the answer is no. If you don't make it past the next paragraph, here's the main thing you need to know about negative rates, they push the stock market up, but do not grow the economy (GDP). As a result, many analysts use stock market growth as a sign that negative rates are good for the economy, when they aren't. The stock market is up because wealth is being forced into the stock market, but there's no growth in the economy. In other words, economies are being pimped by low rates.

In a recent article, I researched what Warren Buffet, Alan Greenspan and Jim Cramer had to say about low and negative rates. There was little agreement. The one thing they all agreed on -- it's not good, and we are in uncharted territory. These same words have been echoed by our past and current Federal Reserve Chairs.

In some ways, they have a point. We are in a period of unprecedented monetary policy, technological growth, overproduction, Brexit, negative rates and trade tariffs. On the other hand, these times aren't really uncharted. If we drill out for a moment, and look at the situation over a longer period of time, we'll see that we have been down this road before. The causes may seem different, but the end result is the same and it has been well documented, especially by a man named Irving Fisher.

Irving Fisher's Debt Deflation Warning

Irving

Fisher was born in upstate New York in 1867. He earned the first Ph.D.

in economics ever awarded by Yale. Although he damaged his reputation

by insisting recovery was imminent throughout the Great Depression,

Fisher attempted to answer the same question we are asking today --

what really happened? Or, in our present case, what's really going on?

He asked this question in hindsight and so had the benefit of clarity.

This clarity told him that excessive debt and deflation are a bad mix. He referred to the phenomena as debt deflation.

Fisher had much time on his hands after losing his family's fortune

and finally came to the conclusion that economic policy had

conveniently left out one fact -- debt greatly exacerbates economic

cycles, especially when mixed with deflation.

Of course,

economists know that debt greatly exacerbates economic cycles. We have

all been taught that too much cash or liquidity leads to high

inflation. So, tools were put in place to prevent inflation throughout

the Fed's massive debt monetization scheme (quantitative easing).

Inflation become the primary indicator of economic performance.

All eyes were on inflation.

When the Fed saw no increase in inflation, it ramped up quantitative

easing even more, which led to overproduction and lower prices. We were all looking for inflation, when we should have been keeping our eye on deflation.

How did we get here?

The initial stimulus back in 2008 created a shock-wave in the market that has only grown in size and amplitude. It is this

shock-wave that Fisher attempted to warn us about some 90 years ago.

He warned us that debt and deflation amplify the market imbalance. In

other words, a regular market can bounce back from a shock. An amplified

market can't because each wave grows in strength until something

breaks.

Time and regret fueled Fisher's research which produced the paper: The Debt-Deflation Theory of Great Depressions.

The paper consists of 49 conclusions or observations made about the

links between excessive debt and economic decline. What makes his

theory unique is that it suggests that the economic decline we're

currently experiencing is due to deflation, not inflation. Fisher

admits that due to the economic theory at the time, he and his

colleagues were all looking in the wrong direction, and at the wrong

signs (sound familiar?). He then suggests that a new theory be added to

explain what occurs when the economy is faced with excessive debt and

lower prices.

The Debt Deflation Theory of Great Depressions

Debt deflation is a phenomena in which excessive debt (or cheap debt)

creates overproduction, which drives down prices. Lower prices leads to

lower earnings, which creates layoffs. Meanwhile, the dollar value of

debt is growing due to deflation. In our case, and unlike in Fisher's

case, the phenomena is further exacerbated by the pace of technology

and automation.

I want to dig a bit deeper into Fisher's most relevant points for today.

First, he felt that there were many causes for market "dis-equilibrium", but only three main "tendencies":

(A) growth or trend tendencies, which are steady; (B) haphazard disturbances, which are unsteady; (C) cyclical tendencies, which are unsteady but steadily repeated. These are tendencies that can throw off market equilibrium.

Fisher then goes on to describe the ubiquitous nature of the market, which is seemingly in equilibrium. This is the same "delicate" market he experienced prior to The Great Depression:

There may be equilibrium which, though stable, is so delicately poised that, after departure from it beyond certain limits, instability ensues, just as, at first, a stick may bend under strain, ready all the time to bend back, until a certain point is reached, when it breaks. This simile probably applies when a debtor gets "broke," or when the breaking of many debtors constitutes a "crash," after which there is no coming back to the original equilibrium. To take another simile, such a disaster is somewhat like the "capsizing" of a ship which, under ordinary conditions, is always near stable equilibrium but which, after being tipped beyond a certain angle, has no longer this tendency to return to equilibrium, but, instead, a tendency to depart further from it.

He goes on to say that:

Under such assumptions, and taking account of "economic friction," which is always present, it follows that, unless some outside force intervenes, any "free" oscillations about equilibrium must tend progressively to grow smaller and smaller, just as a rocking chair set in motion tends to stop. That is, while "forced" cycles, such as seasonal, tend to continue unabated in amplitude, ordinary "free" cycles tend to cease, giving way to equilibrium.

So we know that Fisher

believed business cycles were natural, but what can his observations

tell us about warning signs. Is there anything that would have alerted

Fisher that the Great Depression was looming?

To this Fisher would respond,

...I doubt the adequacy of over-production, under-consumption, over-capacity, price-dislocation, maladjustment between agricultural and industrial prices, over-confidence, over-investment, over-saving, over-spending, and the discrepancy between saving and investment. ...each of the above-named factors has played a subordinate role as compared with two dominant factors, namely over-indebtedness to start with and deflation following soon after; also that where any of the other factors do become conspicuous, they are often merely effects or symptoms of these two. In short, the big bad actors are debt disturbances and price-level disturbance. He refers to these two bad actors as the "price-level disease" and the "debt disease".

While quite ready to change my opinion, I have, at present, a strong conviction that these two economic maladies, the debt disease and the price-level disease (or dollar disease), are, in the great booms and depressions, more important causes than all others put together,

He goes on to make the point crystal clear:

Thus over-investment and over-speculation are often important; but they would have far less serious results were they not conducted with borrowed money. That is, over-indebtedness may lend importance to over-investment or to over-speculation. The same is true as to over-confidence. I fancy that over-confidence seldom does any great harm except when, as, and if, it beguiles its victims into debt. ...On the other hand, if debt and deflation are absent, other disturbances are powerless to bring on crises comparable in severity to those of 1837, 1873, or 1929-33. Why is this? It's because deflation due to excessive debt has a greater impact than inflation due to excessive debt. This is due to its cyclical and compounding nature. Debt creates deflation and deflation artificially increases debt levels.

In

other words, disequilibrium due to market forces tends to create an

initial shock to the system that, over time and like a pendulum, will

slowly work itself back to equilibrium. Disequilibrium due to market

intervention, however, tends to create an initial shock and that shock

is just the beginning. When further compounded by excessive debt, its

oscillations gain momentum with each swing. This is the impact of debt

deflation. It builds upon itself.

In its most

heinous form, deflation (or lower prices) actually pushes up the value

of the dollar, which only adds to indebtedness. As a result, the debtor

is stuck in a loop and can never pay down his debt. Fisher explains it

far better than I can in the following paragraph:

...deflation caused by the debt reacts on the debt. Each dollar of debt still unpaid becomes a bigger dollar, and if the over-indebtedness with which we started was great enough, the liquidation of debts cannot keep up with the fall of prices which it causes. In that case, the liquidation defeats itself. While it diminishes the number of dollars owed, it may not do so as fast as it increases the value of each dollar owed. Then, the very effort of individuals to lessen their burden of debts increases it, because of the mass effect of the stampede to liquidate in swelling each dollar owed. Then we have the great paradox which, I submit, is the chief secret of most, if not all, great depressions: The more the debtors pay, the more they owe. The more the economic boat tips, the more it tends to tip. It is not tending to right itself, but is capsizing.

He goes on to say:

Unless some counteracting cause comes along to prevent the fall in the price level, such a depression as that of 1929-33 (namely when the more the debtors pay the more they owe) tends to continue, going deeper, in a vicious spiral, for many years. There is then no tendency of the boat to stop tipping until it has capsized. ...On the other hand, if the foregoing analysis is correct, it is always economically possible to stop or prevent such a depression simply by reflating the price level up to the average level at which outstanding debts were contracted by existing debtors and assumed by existing creditors, and then maintaining that level unchanged. In other words, the only way to right the ship is to increase prices.

Reflate The Price Level

The market is full. It has eaten everything in sight for the past 10

years and now it needs a moment to pull back and digest, but glutton

has gotten the best of him. The only self-correcting mechanism left for

the Federal Reserve is something that relieves bloat.

In economic terms, the market is asking for a distribution.

It is more commonly known as universal basic income or helicopter money.

Presidential candidate Andrew Yang has rebranded it as the Freedom

Dividend. You can call it whatever you want, but I like to think of it

as a banking and automation distribution. These are the two "bad actors"

that got us here and the market is demanding reparations.

Deutsche Bank

reportedly said that "helicopter money," a term that refers to giving

cash directly to households, "could be highly effective if properly

deployed." Some reports

claim that the Japanese central bank considered dropping payments to

residents, but later decided to approve a $274 billion stimulus

package instead.

Most central banks know we're in crisis mode.

They know we need to raise prices, but they don't know how to do it.

Japan's foray into negative rates in January of 2016 was, in actuality,

an attempt to reflate prices, but they failed, over and over again.

And now, the Federal Reserve is considering negative rates as well.

Thankfully, we not only have the words of Irving Fisher, but our own Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco to steer us in the right direction.

In August, two Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco economists wrote a paper assessing Japan’s experiences with negative rates. The paper was titled: Negative Interest Rates and Inflation Expectations in Japan.

They came to the following conclusion:

Because of the long period of low inflation in Japan, its experience provides an interesting example of the impact of negative monetary policy rates when inflation expectations are well-anchored at very low levels.

...Our results suggest that this movement resulted in decreased, rather than increased, immediate and medium-term expected inflation. This therefore suggests using caution when considering the efficacy of negative rates as expansionary policy tools under well-anchored inflation expectations.

In other words, negative rates

don't work. The market loves them because it means free candy from the

Fed, but the boat is only tipping over further.

The only thing

negative rates are good at producing is higher stock prices, which is

why the market rallied on Trump's negative rate tweets. But, does this

market approval mean the central bank is acting in the best interest of

the economy?

No.

This is the reason Robert Holzmann,

the European Central Bank's newest Governing Council member and

Austrian central bank governor, went on record as saying the ECB's

latest move to lower rates to -.5% was a mistake.

"Frankly speaking," said Holzmann, "I'm not so sure whether we are

playing with the market or if the market's playing with us. Because, if

my economics is right, at the moment the market is gaining for getting more and more in the negative territory,

so perhaps it wants to lead us to believe that's the way. So, I don't

think this market reaction is an indication that this is the way we

have to go."

While it may be hard to find agreement on the calculus behind negative rates, everyone does agree on one thing -- quantitative easing and low rates created an unprecedented amount of debt around the world. Now the conundrum for economists worldwide has become: how do we raise prices after quantitative easing? If negative rates don't work, what will raise prices in a world of overproduction and automation?

Some say the answer is trade tariffs, but while trade tariffs raise prices, they also decrease spending. The only answer the market will accept is cash. Not debt, just cash.

This is anathema to the world's power structure, but it is the only answer the market will accept. It is the only answer that has the strength to keep the ship from capsizing.

In normal situations, giving $1,000 a month to every American would lead to inflation. Ironically, many opponents of UBI actually use Fisher’s theory of exchange to support their argument saying that:

...any increase in the supply of money must result in proportional reduction of the purchasing power of money. Since UBI is bound to reduce the economic output by reducing the workforce participation one could expect price-inflation even if the supply of money remained constant, creating another economic hurdle for UBI proponents in the form of net inflation equal or greater to the overall benefit of UBI.

I couldn't agree more, but we are not in a normal situation. Indeed, the impact of UBI (as described above) is the only thing that can get us out of the current debt deflation spiral we're in. Universal basic income, however much you may not like it, is the only way to reflate prices.